President Donald Trump’s rejection of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) has upended U.S. trade policy, intensifying debate over the effects of trade on employment, inequality, national sovereignty, and safety standards.

Last updated January 31, 2017 7:00 am (EST)

Facebook X LinkedIn Email Backgrounder Current political and economic issues succinctly explained.This publication is now archived. Read CFR's latest backgrounder on the U.S. trade deficit.

The post–World War II era has seen the dramatic growth of international trade and the creation of a global trading framework based on the principle of open economies. The United States has been at the forefront of these changes even as it is less reliant on trade than nearly any other developed country.

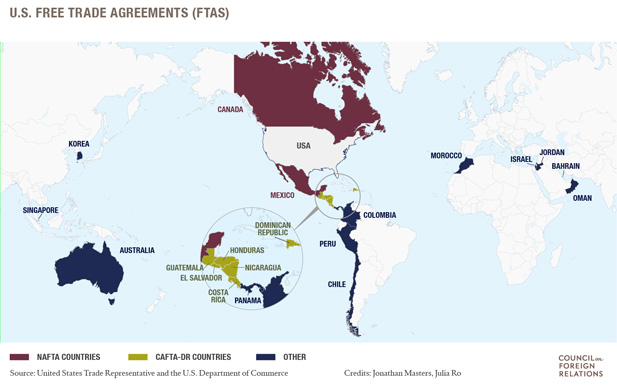

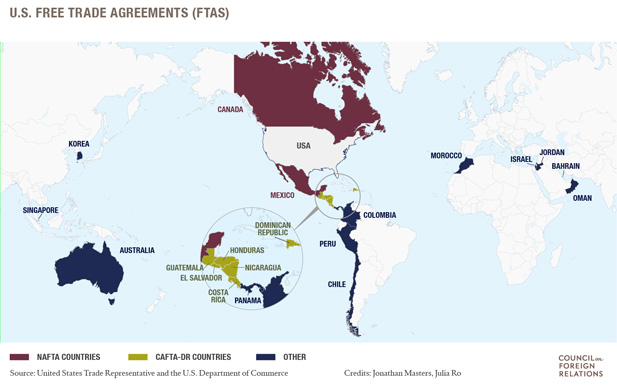

With global trade talks stalling, the United States has increasingly turned to regional and bilateral free trade agreements (FTAs). President Barack Obama won the passage of FTAs with Colombia, Panama, and South Korea, and before leaving office he negotiated the Asia-centered Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and advanced a separate U.S.-EU trade deal. But the election of President Donald J. Trump has upended this trade vision. Drawing on the arguments of many in the U.S. labor movement, as well as some economists, that such trade deals hurt workers and degrade the U.S. manufacturing base, Trump took immediate action to withdraw the United States from the TPP. Advocates counter that multilateral trade agreements create jobs by opening new markets to U.S. exports and making it easier for U.S. companies to compete in foreign markets.

The institutions of global trade policy have evolved dramatically since the end of World War II, led primarily by the United States and its European allies. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) was signed by twenty-three countries in October 1947. By 1986, GATT’s membership had expanded to 123 countries, all of which had committed to the principles of lower tariffs, open economies, and freer trade. Over those four decades, global import tariffs on goods fell sharply, from an average of over 30 percent to under 5 percent.

In 1986, President Ronald Reagan launched the Uruguay Round of negotiations, which created the World Trade Organization (WTO), an agreement finalized under President Bill Clinton in 1994. The WTO was created to address the perceived limitations of the GATT system. World trade had grown increasingly complex since the 1940s, and GATT’s narrow focus on goods left out major areas such as trade in services, agriculture, intellectual property, and cross-border investment.

More From Our Experts

From the perspective of Washington, the question is whether East Asian integration will be led by China or the United States. Beijing has supported a separate FTA for the region, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which would bring together sixteen countries but exclude the United States. Some in the region have expressed similar concerns. The late Singaporean leader Lee Kuan Yew argued in 2013, “Without an FTA, Korea, Japan, Taiwan, and the ASEAN countries will be integrated into China’s economy—an outcome to be avoided.”

CFR Senior Fellow Edward Alden says that killing the TPP weakens the United States’ geopolitical interests in Asia. “Trump has just unilaterally given away the biggest piece of leverage he had to deal with the biggest challenge in the world of trade, which is the increasingly troubling behavior by the world’s second largest economy, China,” he writes. Some Asian countries have said they may try to go ahead with the TPP, potentially by inviting China to join.

Following on the TPP negotiations, the United States and European Union have sought their own megaregional deal, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, or TTIP. The U.S.-EU trade relationship already accounts for more than $1 trillion in flows of goods and services each year. Officially launched in 2013, TTIP negotiations have focused largely on on improving regulatory cooperation between the two sides. Supporters argue this will reduce costs for businesses, thus boosting growth and lowering consumer prices. Another priority is to ensure equal legal treatment for investors.

TTIP negotiations sputtered after the United Kindgom, one of the strongest supporters of the deal within the EU, voted to leave the bloc. Additionally, European leaders expressed frustration with what they say is U.S. unwillingness to compromise on issues such as health and environmental standards. Many Europeans are skeptical about allowing the importation of U.S. genetically modified crops (known as GMOs) and relaxing rules on food labeling, among other perceived impositions on national sovereignty. In August 2016, France said negotiations should be halted and Germany said the pact was "de facto dead." Trump’s election has cast further doubt on the deal.

Supporters had hoped a deal with the EU would strengthen transatlantic relations with a Europe struggling on multiple fronts. Disappointing growth, high unemployment, and persistent sovereign debt issues in the eurozone, along with a confrontation with Russia over Ukraine and the UK’s Brexit, create a precarious situation for the continent. C. Fred Bergsten, the founding director of the Peterson Institute for International Economics and a leading trade advocate, says Europe’s struggles highlight the need for TTIP. A deal “would help energize the reforms that certainly the weaker countries in Europe need,” he says.

The U.S. Trade Representative (USTR), part of the Executive Office of the President, negotiates agreements, but the Constitution gives the legislative branch ultimate authority over foreign trade. Every postwar trade agreement has been passed with Trade Promotion Authority (TPA), previously called “fast track,” through which Congress agrees to give trade deals an expedited up-or-down vote with no amendments.

TPA had expired in 2007 and needed to be renewed for the TPP and TTIP to move forward. Bipartisan consensus on trade has frayed in recent years, and opposition from both parties had threatened to sink TPA renewal. Democrats argued that the sharp decline in U.S. manufacturing jobs, alongside the rise of corporate “offshoring” in countries with low wages and weak labor and environmental standards, showed that U.S. openness to globalization has gone too far.

While Republicans have traditionally been more supportive of the U.S. trade agenda, a bloc of conservatives spoke out against renewing TPA. Some argued that granting the president such “fast-track” powers is unconstitutional, while others echoed concerns of some Democratic members that trade deals dilute U.S. sovereignty by overriding domestic regulation. Other lawmakers have said that any trade deals must address currency manipulation, a practice in which countries purposely devalue their currency to gain an export advantage.

Ultimately, Congress passed TPA in June 2015, jumpstarting the final round of TPP talks. However, Congress failed to hold the necessary yes-or-no vote to ratify the deal, allowing Trump to withdraw by issuing an executive order.

The significance of trade to the U.S. economy has steadily expanded since the 1950s, in line with the broader expansion of global commerce over that period. Today, U.S. exports and imports are valued at more than 30 percent of U.S. GDP [PDF], up from less than 10 percent in the immediate postwar era.

That number is low compared with other advanced countries—only Japan has a lower value of total trade compared to GDP. But trade, and exports in particular, play a major role in supporting U.S. growth and employment. The Department of Commerce estimates that U.S. exports are worth $2.3 trillion, directly supporting 11.7 million jobs. In addition, over 300,000 businesses export their goods or services, 98 percent of which are small-and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) with fewer than 500 employees. [Editor’s note: A deeper examination of the economic benefits of trade can be found in this CFR Independent Task Force Report on U.S. Trade and Investment Policy.]

Some economists argue that TPP and TTIP would have a significant positive impact on the U.S. economy. In theory, giving manufacturers a more level playing field in Asia would boost U.S. exports, while lower-priced imports and the gains in productivity arising from increased competition would be a boon for consumers. The Peterson Institute has released research showing that the TPP would produce annual income gains of $78 billion for the United States. When it comes to the TTIP, the European Commission estimates [PDF] that the deal would add over $100 billion to the U.S. economy and $152 billion to the European economy every year.

For CFR’s Alden, the potential benefits of these deals are based on making it easier for companies to do business across borders. “Multinationals are breaking up their supply chains all over the world,” he says. “You want to give your country every possible advantage to be a location for that investment.”

Leading economists, labor representatives, and consumer rights goups have expressed concern over the impact of trade deals on employment, inequality, national sovereignty, and safety standards. There is also substantial public concern over the effects of globalization: Polling from the Pew Research Center found that Americans’ belief in the benefits of globalization tumbled sharply starting in the early 2000s, although as the economy has recovered, so has confidence in trade.

The economist and Nobel laureate Paul Krugman has argued that the benefits of these “next generation” deals are overstated. Former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers acknowledged that “trade and globalization have meaningfully increased inequality in the United States by allowing more earning opportunities for those at the top and exposing ordinary workers to more competition.” But while some research indicates that the decline of U.S. manufacturing can be partly attributed to the growth of Asian imports, Summers also pointed out that that has little to do with trade agreements themselves. Technological innovation, he says, plays a much larger role.

Critics have raised concerns about both the transparency of the process and the implications for national sovereignty.

Still, many in the U.S. labor movement argue that trade liberalization has caused a “race to the bottom” in workers’ rights and environmental standards. American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) president Richard Trumka contends that the goal of recent trade deals “was not to promote America’s exports—it was to make it easier for global corporations to move capital offshore. The logical outcome was trade deficits and falling wages.” The Obama administration countered that its multilateral deals would have improved labor rights monitoring and enforcement.

Currency manipulation and its impact on the trade deficit, which rose sharply in the 1990s and early 2000s, remains a major worry. China, previously the main culprit, has largely backed off from artificially devaluing its currency, but for the Peterson Institute’s Bergsten it remains important to avoid potential future manipulation.

The Widening of the U.S. Trade Deficit

As a candidate, Trump focused heavily on the lack of currency manipulation provisions in the TPP, and argued that the deal would have accelerated the offshoring of U.S. manufacturing jobs. Leading Democratic and Republican members of Congress also called on the Obama administration to address manipulation. But opponents feared that it could have the unintended consequence of limiting what the U.S. government sees as legitimate monetary policy—such as quantitative easing (QE) carried out in Europe, Japan, and the United States, which also generally has the effect of weakening a nation’s currency. The final TPP deal sidestepped the issue.

Critics have also raised concerns about both the transparency of the process and the implications of the deals for national sovereignty. A provision known as the Investor State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) mechanism, in particular, raised worries that international companies would be able to override local government decisions. Supporters say that the ISDS is no different than the similar clauses used in previous trade agreements, like NAFTA, though those have also drawn criticism.

Ultimately, much of the opposition revolved around the secrecy of the process. Lawmakers had limited access to updates on TPP negotiations, which Alden says led Congress, as well as the public, to complain of being left out of deliberations. “I am increasingly coming to the view that all of this should be done in the open,” he says, rather than “a setup where the corporate interests know in great detail what the negotiating positions are and the members of Congress who have to vote on it don’t.”